I’ve been writing recently a chapter on John Cage, ecopoetics, and mushrooms. At the same time, I’ve been allowed the fortunate position of supervising a dissertation student who is writing about narrative strategies in modernist and contemporary fiction, which will include a study of James Joyce’s Ulysses—and so, alongside my Cage research, I have been re-re-reading Ulysses.

This re-reading of Ulysses is apt, for, as fans and followers of John Cage know, he was obsessed with Joyce, particularly, Finnegans Wake (he called it “my favourite book I’ve never read”), and FW is a text which generated several of his works, among them radio plays:

Roaratorio, an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake. (1979),

Fifteen Domestic Minutes (one male and one female speaker, texts from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake) (1982), and ‘write-through’ text compositions, like “Muoyce (Writing for the Fifth Time through Finnegans Wake)” (1982)[1]. There were three copies of FW on his bookshelf at the time of his death on August 12, 1992. Less well known, however, was his 1992 work “Muoyce II (Writing through Ulysses)” which Sara Haefeli’s 2018 Research and Information Guide cites as unpublished (though there have been premiere performances of the work).

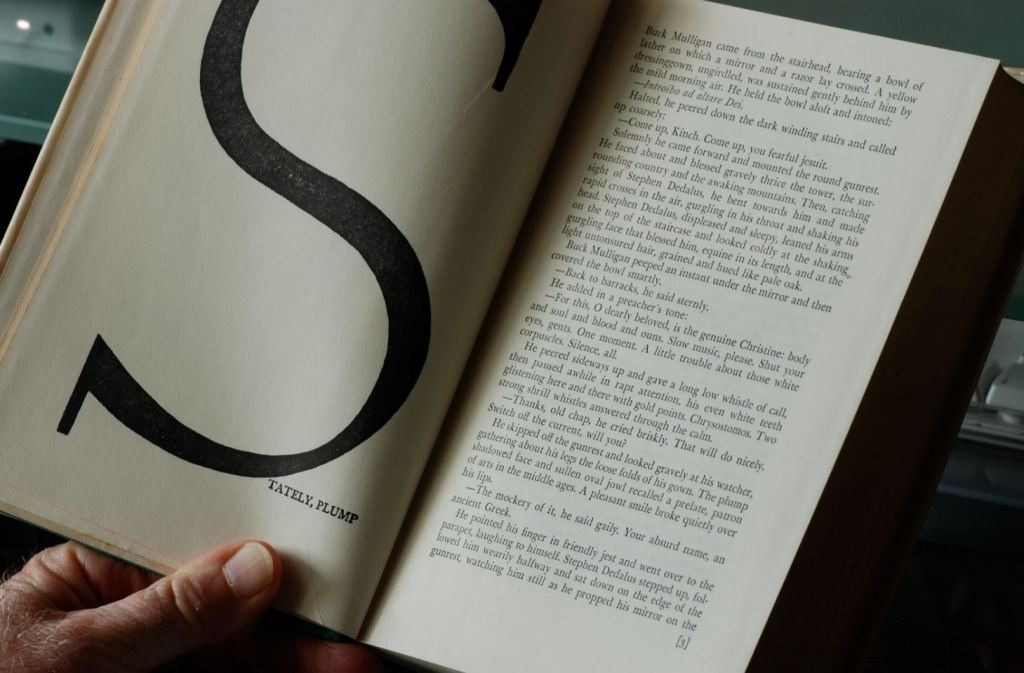

It is easy to see how how the fractal harmonic arcs of Finnegans Wake’s linguistic phonosemy mimic the inescapable ubiquities of intramundane ambience, where everything is everywhere at once in impossible simultaneity. Reading each word of FW is like excavating, dissecting, projecting layers of phonemic etymologies and potential utterances, and reading them together in a synchronic sentence is like a polyphonic cacophony sounding all at once. FW is a musicircus in text-composition form where time, diachronically, collapses on itself and where each phoneme, in an instant, expresses its entire history and possible futures.

At first, a comparison between Ulysses and 4’33’’ might sound unlikely, right? Ulysses (and FW) are texts of excess, abundance—long prose salads which challenge the way we read and force us to adjust our critical protocols, whereas, 4’33’’ is silence, short, empty. Despite its frequent assignation as a ‘silent piece’ (even by Cage himself), 4’33’’ is anything but silent:

I have spent many pleasant hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece, transcriptions, that is, for an audience of myself, since they were much longer than the popular length which I have had published. At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting an identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up within to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being.

from Music Lover’s Field Companion, cited in Fleming (1989) John Cage at Seventy-Five (p. 276)

Here, Cage reflects on shifting 4’33’’ out of the anthropogenic concert hall and into a deterritorialized ecosphere where nature’s echoes, vibrations and movements sound the ‘silence’. The duration of the silent piece, 4’33’’ was chosen for its correlation to popular song lengths, muzacks and the like, and Cage’s reflection on his re-performance of the silent piece ‘much longer than the popular length’ brought to my realisation that the fixed timeframe was variable in relation to its performed environment, making the ‘silent piece’ a much more appropriate title for the work than 4’33’’, which refers to just one possible performance context.

Ulysses, while a less linguistically complex prose texture than FW, takes place over the course of one day in Dublin, 1904, in quasi-linear time from 8am to 2am (there are skips, for example, ‘Part II’ re-boots the narrative timeframe back to 8am). This compositional device presents the same sort of constraint-based frame as 4’33’’—a fixed start and end point in which the extraordinary intramundane happenings of that day in 1904 expand and flourish. The texture of the prose narration is often chaotic, difficult, noisy, intertextual, but the novel’s structure is formal and organised around eighteen episodes (parallel to Homer’s Odyssey) which constitute a ‘schema’, adding further constraint to the process. And so, might it not be plausible that Ulysses inspired the constraint-based process of 4’33’’?

[1] I have written about Cage’s ‘writing-through’ and mesostics in more detail here. Or read Marjorie Perloff on the subject here

Leave a comment